Mr. Motoharu Ueda of Culture Convenience Club Co., Ltd., who views more than 300 exhibitions a year, visited the Neighbouring Textures exhibition, held at the Honjima Refuge on an island in Kagawa Prefecture. In this interview, we ask him what it was like to view photographs—capturing the shakkei (borrowed scenery) of the Honjima Refuge and other locations—within the physical space itself.

Interview and Text | Yoko Kawamura

Photography (Portraits and Exhibition Spaces) Misaki Yanagihara

Proposing a Way of Living with Art

Your social media suggests that you attend a remarkable number of exhibitions each year. Could you tell us about the nature of your work?

I joined Culture Convenience Club Co., Ltd. (CCC) in 1997. In 2017, the company took on a new mission to develop art as a business, and since then, I have been involved in creating stores and content centered around art. CCC was founded in 1985 and had primarily operated a rental-based franchise business until then, so accessibility to the stores was crucial. That's because, with videos and CDs, you have to return what you borrow.

However, times were changing. Our founder, Muneaki Masuda, embraced the philosophy of “creating comfortable spaces,” which led to the opening of Daikanyama Tsutaya Books. Rather than functioning as a conventional general bookstore, it embodied the concept of a store centered on lifestyle proposals, featuring concierges who are professionals in their specialized fields.

I see. So, that was how CCC went through its renewal.

As part of those lifestyle proposals, CCC decided to create Ginza Tsutaya Books inside GINZA SIX, built around the themes of art and Japanese culture. Around that time, we brought in teams with expertise in art—such as Bijutsu Shuppan-Sha, the publisher of Bijutsu Techo, and NADiff, known for running museum shops. That’s how CCC Art Lab came together—a creative team that proposes a way of living with art.

Within the team, I focus on business strategy and oversee project management. The underlying idea is that combining bookstores, publishing, and media might lead to something new.

Experiencing Mitate through the Tea Ceremony

What was your impression of the Neighbouring Textures exhibition?

When I visited Honjima, it was a drizzly, chilly day in March. What left a particularly strong impression was the tea gathering led by Mr. Norio Tohyama, a scholar and architect of tea rooms. I was served matcha in a black tea bowl, and as I brought it up to my face—you know how you do—I glanced out at the garden beyond the glass sliding doors. And then I looked down at the tea and thought, “Wait, it’s the same!”

Do you mean it felt like a mirror?

Within the deep brown window frame—almost black—of the wooden building, the lush green garden extends beyond. And that very scene in front of me also seemed to be right there in the palm of my hand. When I brought the bowl close to my face, it felt as if the two images merged perfectly. It all just clicked that this is mitate in the tea ceremony. When I told Mr. Tohyama how striking I found that experience—of seeing something not as what it is, but as something else entirely—he explained that, in a typical tea gathering, the outside world is shut out so that one can quietly focus on the tea within the intimate space of the tea room. But on that day, he had intentionally opened the fusuma panels, making it a special occasion.

That experience in the tea gathering set the tone for how I engaged with the exhibition afterward. Through the concept of mitate—the art of visual allusion in Japanese aesthetics—I was struck by the beauty of those moments when what is right in front of you overlaps with what lies beyond.

A Multi-Layered Photography Exhibition

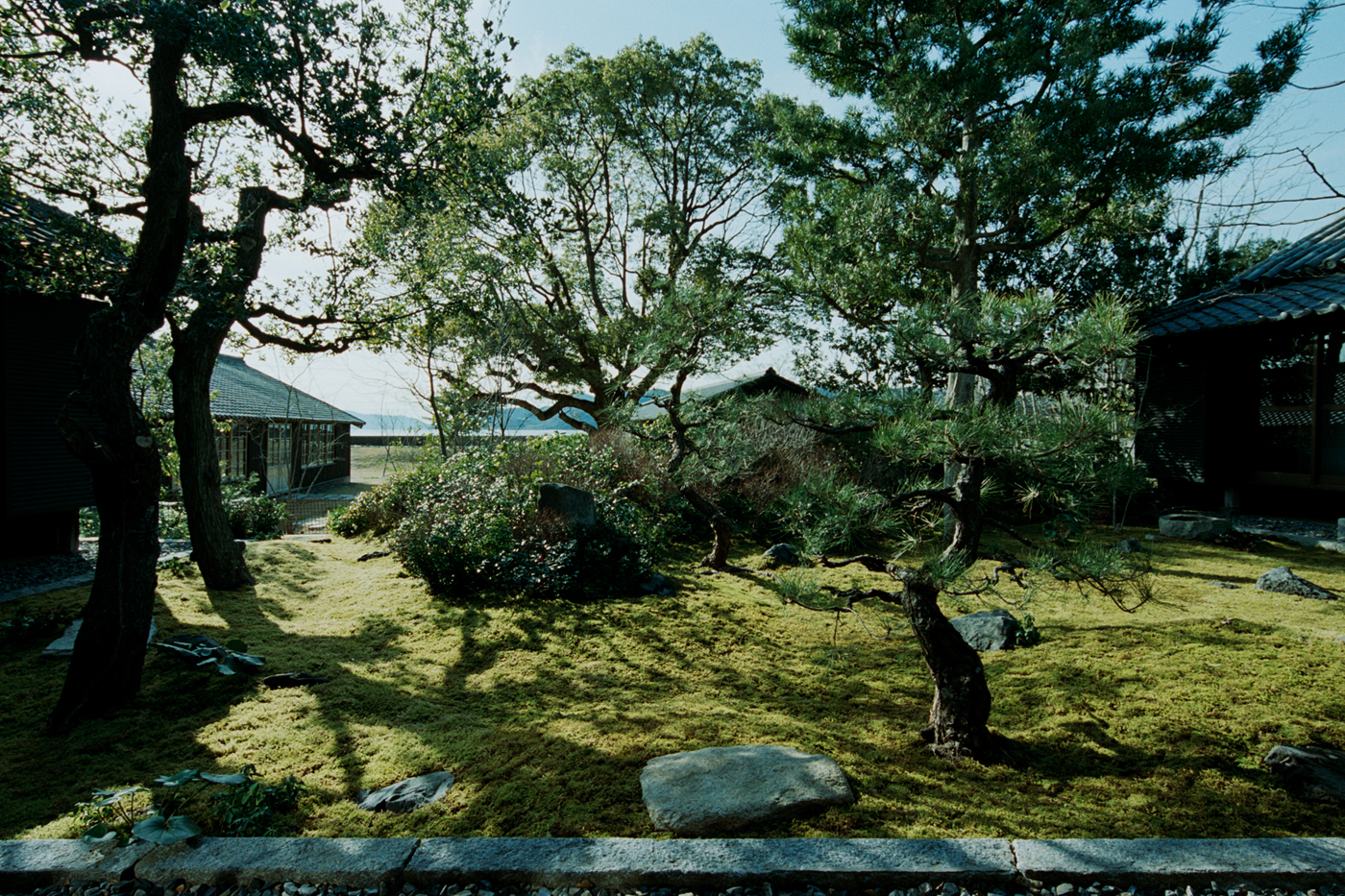

The exhibition itself had a multi-layered structure: viewing photographs taken at the Honjima Refuge within the very landscape they depicted. It was a photography exhibition, but what appeared in the photographs was the garden right in front of us. In the Moss Garden, for instance, the scene evoked the Seto Inland Sea, with islands seemingly floating on the surface. So, the garden itself was also a mitate—a reinterpretation of the surrounding landscape. It all formed a kind of meta-structure.

What was it like to be inside such a meta-structured exhibition space? When there are multiple things to take in at once, did you feel that your senses and the space were expanding outward—or rather, being drawn inward?

It was really both. The gardens at the Honjima Refuge have a lot of deliberately unfilled space—nothing feels overgrown or dense. Maybe it’s because I’ve been reading Le Jardin en Mouvement (Misuzu Shobo, 2015) by the French gardener Gilles Clément, but I felt as though the plants in the gardens had been arranged with the idea that they would grow and evolve on their own from that point forward. Not in the sense of tightly controlling every element, as in some traditional European-style gardens, but more like responding to what the plants might become—imagining how they’ll grow in the future.

Japanese gardens are often enjoyed in their fully matured, almost completed state—there’s a sense of appreciating the time that the garden has already lived through. But the gardens at the Honjima Refuge felt different. Rather, they invite you to look at them while imagining what they might become in the future. So, it felt like time was moving both forward and backward at once—and I wasn’t sure if my physical senses were expanding or just getting all mixed up. [laughs]

It reminded me of Ted Chiang’s Story of Your Life (Hayakawa Publishing, 2003), which envisions time not as linear, but as circular—as if the present and the future exist simultaneously. It felt like I was backcasting from the future. There were so many layers to read into—everywhere you looked—and I found it absolutely fascinating.

I see. The buildings at the Honjima Refuge come from different periods, so it’s easy to imagine how they might evoke an awareness of the past—but I hadn’t expected that they could also evoke a sense of the future.

The photographs are by Mr. Kentaro Kumon, while the space is designed by Mr. Makoto Yamaguchi—so they offer different perspectives on the same place. Of course, I think there’s also a shared sensibility between them—something that’s been cultivated through their Duo’s Journey. One of the key points of this exhibition, I think, is that the photographs include not only the Honjima Refuge but also MONOSPINAL. It’s not just that the photographs overlap with the actual garden in front of you—what’s striking is that the inclusion of the modern building in Asakusabashi, designed by Mr. Yamaguchi, reveals a continuity in the way both spaces are seen.

There is a photo of the exterior of MONOSPINAL’s first floor. A tilted utility pole stands in the frame, and it looks like an old tree to me. I’m not sure if it’s right to call it mitate, but somehow, the utility pole started to look like an old tree to me, and the wires were like vines. And it’s not just something that happens in photographs—sometimes it happens when I’m just walking around my own neighborhood. Since I started to see things that way, the everyday cityscape has taken on a new look for me.

That’s why I think shakkei is not only something intended by the creator, but also something that’s interpreted by the viewer. That kind of thinking often leads to the idea that we should simply appreciate the natural beauty of the Seto Inland Sea—but that’s not really what I mean. I think we can also find something meaningful in urban elements like utility poles and wires. It’s not a simple dichotomy where nature is good and artificial things are bad.

At the end of the day, a garden is an incredibly artificial thing, isn’t it? Nature is all around us, and yet we deliberately construct imitations of it to appreciate. Besides, even materials like glass, metal, and concrete ultimately come from nature. Thinking along those lines, I feel like we’re actually living within a gradient. And if we have the perspective to recognize it, maybe we can take in the world around us in more nuanced and richer ways. I think that connects to how Mr. Yamaguchi and Mr. Kumon, during their visit to Koishikawa Korakuen, perceived Tokyo Dome—not the mountains—as the shakkei. I think that kind of perspective not only changes how we see the landscape, but also opens up a broader sense of personal comfort within it.

Bringing Matière into the World

Since going to an exhibition means setting aside time from your already limited day, there’s always that choice to go—or not to go. Do you have any personal criteria or guiding principles when it comes to making that decision?

When I decide to go to an exhibition, it’s not from a collector’s point of view. I think I choose what to see based on whatever questions or concerns I happen to be carrying with me at the time. I haven’t thought about it too deeply, but I think it’s because I see things like art, music, architecture, and film as a way to engage with society.

I’ve been into music since I was in junior high—not just enjoying how it sounds, but was also drawn to the backstory of why the artist created a piece. When I was listening to music from other countries, I’d often read in magazines about the culture or social issues behind it. It’s through music and other things that draw me in that I’ve been able to connect with the society behind them. And I guess, in the end, it wasn’t really books that I loved—it was bookstores. Sometimes, just browsing the covers of books and magazines, you start to feel things connect in a way you can’t quite explain. Certain keywords start to connect, and you get a glimpse of what’s in the air right now.

With all that in mind, what kind of background or underlying ideas did you sense behind the Shakkei—Neighbouring Textures project?

Earlier, I mentioned Le Jardin en Mouvement, and according to Niwa no Hanashi (Think as a Garden, Kodansha, 2024) by Tsunehiro Uno—which applies Gilles Clément’s ideas to contemporary society—the book isn’t just about gardens. It’s also about society and communities. Rather than a neatly ordered garden, a living, ever-changing one requires us to listen to it and respond—much like how we might engage with society. Social media is a given now, but when internet technology first emerged, people were talking about a kind of utopia, where you could communicate freely with anyone around the world. But instead, what we have now is a really harsh space—full of hate, conspiracy theories, and all kinds of hostility. Why is that? In Uno’s argument, one of the ways he suggests we might change this situation is through the idea of the “garden.” What matters is making something with your own hands.

It’s not some grand statement that everyone has to become an artist—what the book suggests is that creative acts, like tending a garden, are ways of engaging with the world. I feel that this kind of hands-on engagement with the world is what gives it a sense of matière—a tangible texture. And maybe that’s exactly what resonates with Shakkei—Neighbouring Textures. That’s why I think it’s not only about the landscape itself, but also about what we sense behind it—something that goes beyond just the visual. Maybe that’s what gives the world its texture—what matière really is.

An Experience Only Possible Here

What kind of possibilities do you see in this project?

I feel that this exhibition was an experience made possible precisely because of this place. I felt that the Honjima Refuge—including the place itself—was part of the artwork. A work that captures the Honjima Refuge is placed within the Honjima Refuge itself, and the garden incorporates the landscape of the Seto Inland Sea. That layered and gradational structure is, in itself, an essential part of the work’s artistry—and Neighbouring Textures seems to be a self-referential expression of exactly that idea.

There are no clear boundaries between materials like wood and stone, or between architecture and plants, or the artificial and the natural. As matières, they exist side by side, interact, and merge seamlessly, allowing the space as a whole to emerge as a single, cohesive work. Everything moves beyond fixed roles—like protagonist and background, or inside and outside—and instead exists side by side in a gentle, parallel arrangement. Mr. Yamaguchi and Mr. Kumon, I think, are drawn to the beauty found in the way things sit side by side.

As long as the Honjima Refuge maintains this structure, the works on display can be interchangeable. As new experiences unique to that place continue to unfold, time and human memory will gradually accumulate. Still, none of it can really begin unless you go there yourself. It’s not meant to be a tourist attraction, but it’s also not something that should only be understood by a select few. Ideally, it’s something that could also resonate with the local community.

The Honjima Refuge is “a quiet realm” that evolves with the rhythm of the seasons. What we’re aiming for is to create a gentle connection with those who might resonate with this place—and with the way of thinking behind it. It’s the kind of project whose impact on society isn’t immediately obvious—more like planting seeds. Perhaps that’s exactly why it has the potential to create lasting value.

March 26, 2025