DUO’S JOURNEY

Tokyo MONOSPINAL

MONOSPINAL is an office building for a game production company, emerged in 2023 in Asakusabashi, Tokyo. The architecture designed by Makoto Yamaguchi is surrounded by nine layers of sloping walls, making it impossible for passers-by to get a glimpse of the interior. All facilities, including security, are centrally controlled by a tablet PC. The inverted-slope walls that open up to the sky control the sound, light, and wind from the densely populated surroundings with an elevated railway and multi-tenant buildings to offer an environment where the users could concentrate on their creations.

Interviewer/writer: Yoko Kawamura

Kumon: There are many things to focus on. I took many photographs of the same places, but the thinking behind each time was quite different. For example, this exterior wall can look dramatically different just by moving the camera slightly to the left or right. Naturally, the texture of the colour also changes according to the time of the day. When the yellow colour fades, the tone is cooler. In the evening, it becomes a little more emotional. I struggled with such interpretation in printing.

I see that is how much influence from the outside world can reflect on architecture.

Kumon: That’s right. You can’t get the full picture by looking from below, but it still does have an impact. At first, I was worried about how to photograph it; but once I had started, it was fun.

Yamaguchi: The building is a combination of multiple materials, including panels and glass. However, I was surprised at the various expressions discovered through how Mr. Kumon captured them. I think that is precisely how I wish this building was viewed.

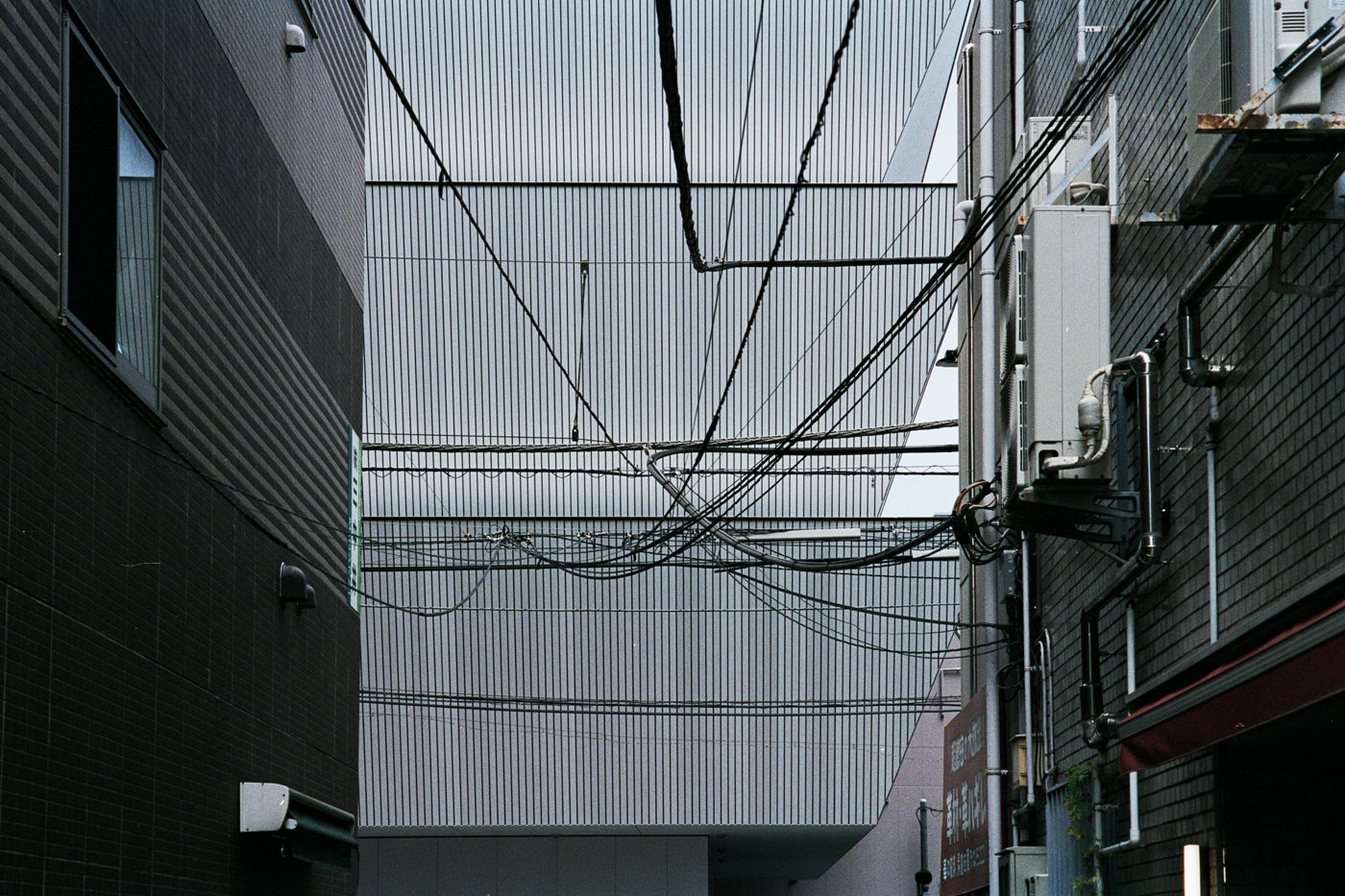

Kumon: It wouldn’t have turned out like this if it was before we started the Shakkei—Neighbouring Textures project. This is actually the first photo I took. The moment I saw this, I thought the electric wires looked cool. When I realized I was feeling that way in this session about what we conventionally would want to exclude, such as electric wires, I knew I could photograph them in any way possible and succeed.

Yamaguchi: There are many places in Asakusabashi where electric wires are tangled like this. With the elevated railway in its front, I think this photo symbolizes the unique image of this crowded town.

Kumon: Rather than putting MONOSPINAL in the center, I tried to photograph it as part of the landscape. That is when I discovered once again that there are no straight lines in nature. The horizon is not a straight line, nor can you find one in human bodies. So, when I thought about where I could find a straight line, I could only imagine gravity, like an apple falling, though I’m not an expert on anything. Electric wires would naturally droop, and shadows of buildings tend to fluctuate.

Yamaguchi: That’s true. So many electricity poles are also slanted.

Kumon: Exactly. That’s why I thought MONOSPINAL, which consists solely of straight lines, would become a symbol in a town full of curves.

Yamaguchi: I see. When we hear the term “symbol,” we generally imagine something symbolic, like a landmark. However, in this case, we can’t see what’s happening inside, which gives this tranquil impression in the sense that it doesn’t provide any information. I designed it hoping it would become part of the landscape, so I feel like that may have worked.

Kumon: Although, when I first saw it, I was struck by its presence (laughs).

When you previously photographed the Hama-rikyu Gardens , I remember the photo of a one-story building in a Japanese garden set against the backdrop of a forest of modern buildings. Trimming the signboards at the top of the buildings made it less descriptive, which gave the architecture a certain sense of abstraction, resulting in a photograph where both the garden and the modern buildings are the main subjects. I believe what you realized at the time is relevant to what you said earlier; to what extent did you intend to “not offer information”?

Yamaguchi:

In this case, that was the most crucial part of designing the exterior. I thought a part of the reason that sceneries don’t emerge around buildings is because we can tell what they are for. Office buildings would have their company names written on signboards. But because this building doesn’t have one, it looks like a sculpture that we don’t know what it is for. In other words, the meaning disappears to the outside world.

I think another key is its monotonous nature. Basically, it is a repetition from the bottom to the top. It traces the law of nature where a trunk grows into branches and then comes leaves. The exterior walls are made by stacking thin aluminum panels with a finishing process called shot blasting, where tiny iron shots are blown onto the surface, creating countless dents. This makes the surface slightly duller in terms of light reflection. There are these hidden construction processes to enrich the textures, and I think you discovered those diverse expressions for us.

Kumon: Now I see why I found so many parts with color gradations. It’s true that if you are like, “Oh, it’s an apartment building,” and see the function right away, it doesn’t fulfill its role as shakkei. Perhaps it’s crucial that we don’t know what it is.

Yamaguchi:

Medieval towns in Europe are lined with rows of similar buildings, where some of them are utilized as hospitals or hotels, and their functions can’t be defined from the building exterior. I think that is why we don’t process each building as information but can see the entire town as a single scenery. Of course, we have this Tokyo-esque messiness of a scenery. However, in terms of creating calmness, I think it’s vital that the building itself be silent, or in other words, provides as little information as possible.

For this project, one of the most relevant conditions was the elevated railway nearby and multi-tenant buildings surrounding the site. The railway is right in front of your eyes on the third floor, and a train will pass every 1.5 minutes on average.

Kumon: You can even see the building from the platform of JR Asakusabashi station.

Yamaguchi: When we went to Katsura Imperial Villa, we saw how the site was surrounded by a low bamboo fence. The inside is a protected space where the Emperor once lived, but there is a bamboo forest, then a bamboo fence where a public road runs naturally right next to it. Referencing such a scenery, I tried to connect the site to the surrounding space by creating the least boundaries. By not creating a boundary or a clear prohibited zone, I thought it would feel better to have a loose connection between the inside of the site and the public space outside. So, instead of building a fence, I imagined putting up a spiritual barrier around it. That is why we have the pine tree and stone wall on the southeast corner near the main entrance, while a large rock and bamboo grove is on the northeast corner.

Yamaguchi:

While we placed rugged rocks on the outermost part connecting to the local streets, we covered the inner part with flat tiles. Rather than abruptly neighboring the inside and outside, we created a buffer zone to gently connect them. The colors are also selected to create a gradation of grey. The building adopts a seismic isolation structure, which prevents it from shaking as much in the event of a large earthquake. However, because the area around the building would still shake, the outermost part of the flat tile is left movable to absorb the motion. The conventional option would be to emphasize the range of movement by adding differences in height or materials. However, we encapsulated the functionality within the material because we thought highlighting the function would add another piece of information.

Also, instead of creating a large building using large modules, we tried to imitate how natural objects are made, and collect smaller pieces to make large-scale things. The exterior walls are made of custom-made molded thin aluminum panels that are installed one by one on-site by hand. So, it makes me happy to see the collection of details like floorings, walls, and plants captured in the photographs.

So, in that sense, you couldn’t have created this gradation using plants with rounder leaves?

Yamaguchi: That’s right. We selected plants with long slender leaves, such as pine, bamboo, silver grass, and juniper.

Kumon: I see. When I took the close-up pictures of the materials, I felt they reflected the Yamaguchi style. No matter how many elements are involved, I always hope that Mr. Yamaguchi’s ideas will take shape. We ended up with so many full-shot photos, but I think it is because I like the ones that give a sense of the city.

Yamaguchi: The one with the silver grass in the foreground and the pine tree in the back is the photo that makes me happy. Silver grass is considered weeds and rarely makes it in the same frame as pine, which is considered to have a formal status in Japanese gardens.

Kumon: When I photographed on a Sunday morning, I saw quite a few people walking past. However, when I finally selected the photos, I preferred the ones without people. When there are people, you start to see a narrative or a protagonist. Instead, it’s enough to imagine what kind of a person lives there. The scenery becomes a scenery by including people, but for this particular project, I felt otherwise.

Yamaguchi: The same can be said about the previous photographs from the Japanese gardens. Maybe it is about having one too many pieces of information. The image of people is so strong that it could add noise when we try to observe neighboring textures.

Kumon: That being said, I have to say the presence of Ramuchan (a grilled mutton restaurant) is astounding (laughs). Architects usually would hate it.

Yamaguchi: I might have felt that way when I was younger, but now I feel like the gray color of the facade is matching.

Kumoni: The lines on the walls are also matching. They look quite similar actually.

Yamaguchi: One doesn’t exist for the other to stand out. I like this situation where the hierarchy vanishes between the architecture, the surrounding stores, and the electricity poles.

December 27, 2023