DUO’S JOURNEY

Kagawa honjima Refuge

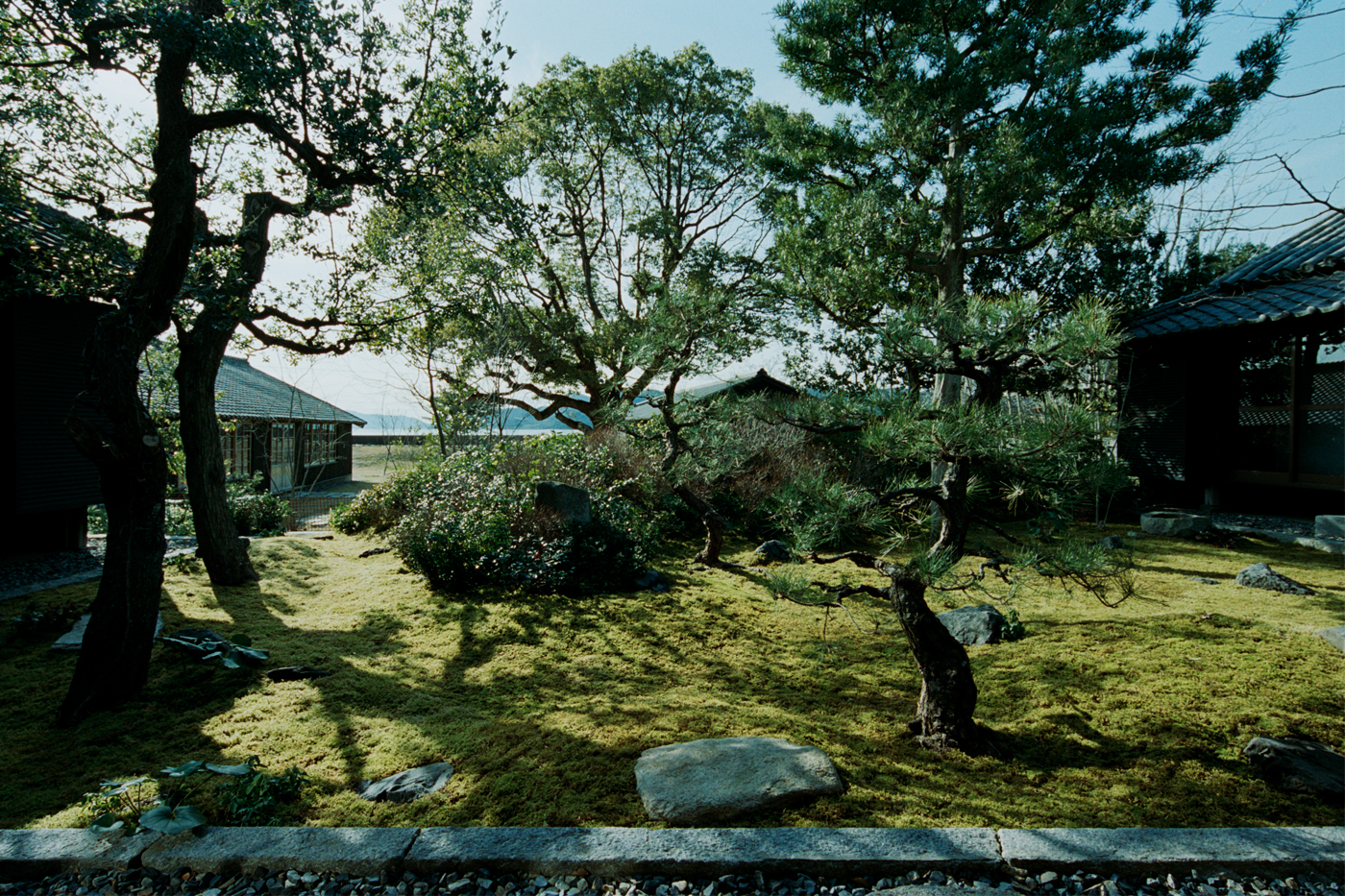

In the Seto Inland Sea floats the Honjima Island. Located on this peaceful island in Kagawa Prefecture with about 300 people, the Honjima Refuge has a site of over 3,300 square meters with buildings built between the Meiji and mid-Showa periods and three Japanese gardens: the gardens of Miscellaneous Trees, Moss, and Bamboo Grass designed by architect Makoto Yamaguchi in collaboration with landscape designer Naoki Nishimura.

Interviewer/Editor: Yoko Kawamura

Yamaguchi: About 25 years ago, I was moved by the beauty of the Seto Inland Sea that I saw on my way to Naoshima, and I have always wanted to create a place where I could spend time gazing at that scenery. I started looking for a specific location around 2019, and the Honjima Refuge project set sail in 2021. The buildings were virtually a ruin, and we had issues unique to remote islands, such as procuring craftspeople and materials, and the ferry schedule affecting our working hours. It took us a long time to start the construction. While contemplating what to keep, we started repairing the leaking roof because of missing roof tiles. That was when we called on the landscape designer Naoki Nishimura and immediately started working on the garden.

Kumon: I visited the Honjima Refuge in the winter and summer of 2023 and the spring of 2024. On my first visit, the architecture was stunning, but the gardens were not quite done yet. I have the impression that the plan has gradually changed since then. I always saw Mr. Yamaguchi as a perfectionist, but even if I do not go so far as to say he was winging it, he was constantly embracing changes. I understood that that’s what it means to create gardens. Most Japanese gardens I have visited are over 100 years old and in a state that could be called complete. However, the gardens here changed rapidly during the construction. I saw how the forces of nature are powerful in such an island environment.

Yamaguchi: I have created gardens as exteriors for architecture, but this was my first time constructing a Japanese garden, and I have learned a lot. I am not trying to recreate the old appearance, but rather to create a “better scenery that may have once been there.” For the architecture of Honjima Refuge, I merely restored it, but I put a lot of work into the gardens as they were completely run down. If you stop tending the plants and pulling out weeds, they will grow out of control, moss will disappear, and the gardens will fall apart immediately. Therefore, I had to think from scratch, but I struggled to find a starting point, unlike the process in architecture. I first tried to create something that would connect with the sea, mountains, rocks, and plants on the island, and when that hypothesis started to take some shape, I asked Mr. Kumon to come.

Kumon: When I first arrived, plants like bamboo grass had not grown yet, and the Garden of Miscellaneous Trees was still called the Moss Garden.

Yamaguchi: Then, Mr. Kumon did not take many photos of the places I had doubts about. In particular, the Moss Garden. I had organized the original lanterns and stones, but it still felt more like an unremarkable garden you see in your relative’s home rather than a proper Japanese garden. And he didn’t take photos at all (laughs).

Is that what inspired you to plant moss in all three gardens?

Yamaguchi:

That is right. First, I went back to thinking about what is placed next to what. As Mr. Kumon mentioned, I know it’s a bit confusing, but the Garden of Miscellaneous Trees and the Moss Garden were initially called the opposite. The former Moss Garden was a surrounded space like a courtyard where various species of trees grew, but the impression of the moss covering the entire surface was strong because it was an enclosed place.

In comparison, the former Garden of Miscellaneous Trees had a cluttered impression with trees and stones scattered around, making it difficult to find what to focus on. I realized that the former Moss Garden was outshining the former Garden of Miscellaneous Trees. It was evident in Mr. Kumon’s photos, which revealed the challenge of making the three gardens, including the Bamboo Grass Garden, have equal weight. This is why I decided to plant moss in the former Garden of Miscellaneous Trees.

This is not something that only applies to gardens, but I believe the impression of a space is determined by a floor rather than walls or a ceiling. The simple act of laying a carpet on the floor can change the atmosphere drastically. After planting moss, the former Garden of Miscellaneous Trees gained a stronger presence of the moss, and the characteristics of each garden were clearly defined, so we finally decided to switch the names.

The moss created a sense of equality and brought out individual characteristics. What type of moss did you use?

Yamaguchi: It is something Mr. Nishimura taught me. Since the site is near the coast affected by salt damage, and we did not know which species could adapt to such an environment, we mixed and planted three types of moss. By mixing mosses with different characteristics, I heard that the species that best suits the environment could take root over time. I assume the moss in the former Moss Garden survived by being surrounded by four walls. I saw the gardens were not good enough for Mr. Kumon to take photos of, which led us to plant the moss.

Kumon:

I was more prepared to take photos of the buildings, rather than the gardens upon my first visit. As I listened to Mr. Yamaguchi explain the project, I began to see what I needed to photograph. It was partly due to the change in my mindset, but I think the biggest factor was the change I saw in the gardens. By the third visit, I felt like the angles were automatically determined.

For instance, when I photographed the Moss Garden, I looked through the viewfinder and felt connected directly to the sea. I saw the islands floating on the ocean in the distance, the ookarikomi (bushes and trees planted together and pruned to make a single hedge) hedges that resembled the archipelago in the middle, and pine trees and rocks in the foreground. The light reflected on the ground where the moss was planted, emphasizing the silhouettes of the trunks and shadows of the three pine trees. It felt like the elements were resonating with each other. It would not have turned out like this if the ground was darker. Also, the buildings on both sides worked as a frame in the foreground, creating an immense sense of depth.

Kumon: So, I didn’t mean to refuse to take pictures because the gardens were not completed. Rather, because photography deals with reality, I think the camera will naturally be drawn to it when it is ready. Mr. Yamaguchi never explains his intentions before the shooting, but I feel that they naturally emerge without receiving any explanation and each tells a story according to their names. It is very satisfying to take pictures of a highly condensed microcosm that feels like “everything is in here.”

Yamaguchi: I see, that is great to hear. If one cannot understand without my words, it means the gardens do not look the way they were intended.

Kumon: The pavement in the Garden of Miscellaneous Trees continues straight ahead, which also allows the breeze to pass through. As the walls in the background are dark brown and almost black, the background of the plants becomes darker. So, although there are many different plants, the view is not so clumsy, making the plants appear sharp and beautiful as if framed. Was that your intention?

Yamaguchi: The other gardens have wider views, so I tried to add as many walls as possible here. The walls are made using yakisugi, a traditional technique of carbonizing the surface of cedar to increase its durability. It has been used commonly on the islands of Seto Inland Sea for cladding houses. It is initially black, but the color fades over time and becomes dark brown. I think that by surrounding the garden with black walls, the plants in the sun are highlighted, which vivified the space.

What kind of place is the bamboo garden?

Yamaguchi:

First, when you enter the back alley from the road, there is a gate with nagaya row houses on both sides. Then you pass through the Garden of Miscellaneous Trees to approach the entrance, which, in a way, makes the Garden of Miscellaneous Trees the entrance itself. The Moss Garden faces the sea, and when you open the sliding door at the end of the pavement in the Garden of Miscellaneous Trees, you can see the sea faintly beyond the Moss Garden. However, you cannot see the sea from the Bamboo Grass Garden located by the private room in the Main Building.

The hedge blocks the view with a lush mountain in its background. This photo was taken from a seated height, but if you stand up, you will see the ocean panorama spreading below the mount. In other words, there is an invisible sea here. The three gardens gained the same condition by planting moss, but the ocean as the shakkei (borrowed scenery) is treated differently. I finally understood that this was what I wanted to do the whole time.

Yamaguchi: But you cannot experience them at the same time. You catch a glimpse of the sea, look at it, and finally feel it even though you cannot see it. In this way, you are looking at the garden while the memory of the sea remains in your mind.

Kumon: The presence of the sea can always be perceived through sound, light, and humidity. The area where the Honjima Refuge is located is so tranquil that birds chirping is the only sound you can hear besides the gentle rippling waves unique to the Seto Inland Sea.

Yamaguchi: The presence of the sea is indeed huge. I think the distinctive feature of this place is that the sea is neighboring each garden in different quantities.

August 8th, 2024