DUO’S JOURNEY

Kyoto Ninna-ji Temple

Ninna-ji, a temple of Shingon Buddhism, was founded in 888 C.E. in the Heian period. Figures from the imperial family served as priests here until the Taisho era in the early 20th century. The garden comprises the north and south gardens on opposite sides of the lecture hall, with the north garden having a five-story pagoda as shakkei being designed in its present iteration by Jihei Ogawa VII. The cherry blossom and tachibana trees planted in front of the ceremonial hall (or shinden) in the south garden are similar to those planted in the Shishinden of the Kyoto Imperial Palace. The garden is designated a Place of Scenic Beauty by the national government and also registered as a World Heritage Site.

Could you talk a bit about why you visited Ninna-ji?

Yamaguchi: In Ninna-ji’s gardens, there’s a five-story pagoda that serves as shakkei, but when I got there, the area between the garden and pagoda was under construction and covered with a blue tarp, obscuring the shakkei. You could see the pagoda from a different vantage point, but it just looked so small. But even from that vantage point that diminished the pagoda, Mr. Kumon was very excited to see all the pine trees.

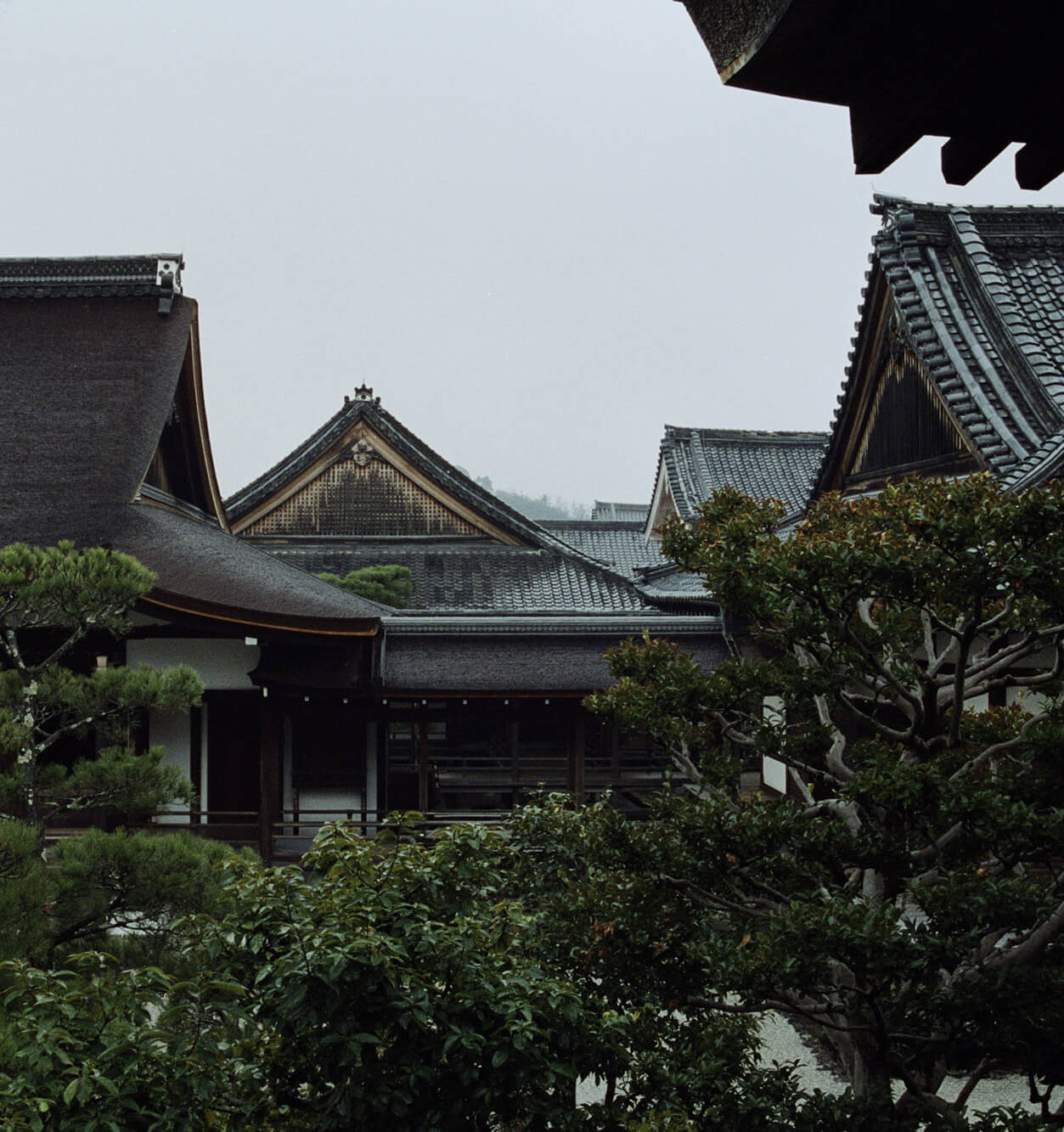

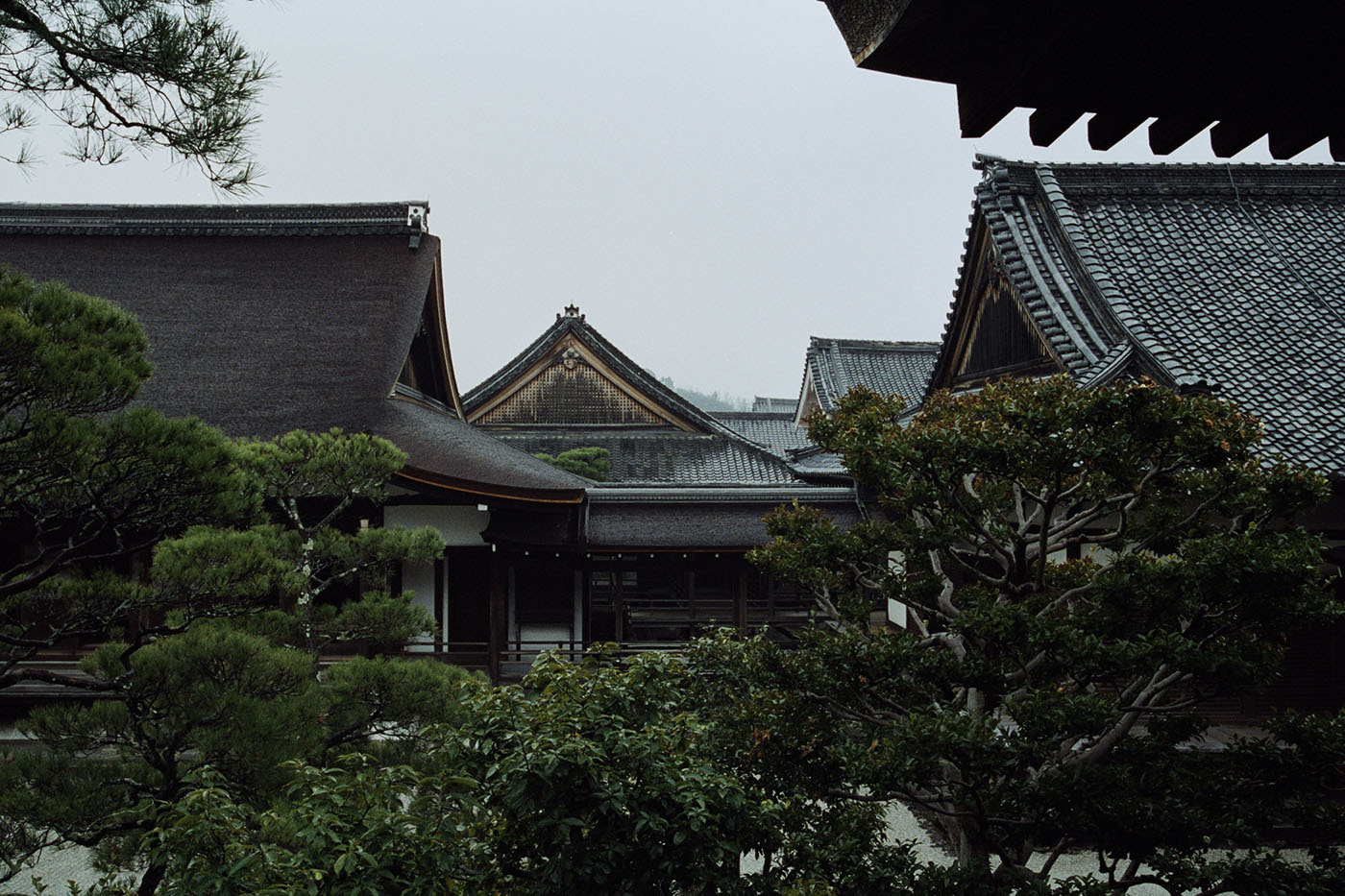

Kumon: The pine trees at the entrance floored me from the get-go. They look incredible. And it was raining that day, and the wet greenery was beautiful. In my mind, what was more interesting than shakkei was the composition of the low pine trees spread out like an ocean, the tall trees sticking out from that ocean like lightning bolts, and the pagoda beyond the sea of pines.

There’s a difference between small, concentrated gardens and large, expansive gardens. How would you say you enjoy a large garden?

Yamaguchi: I don’t know if people in those days walked around in a daimyo’s garden. Korakuen for example has a very large area with rice paddies and lawns, but those may have been vacant spaces meant less for walking and more for viewing from far away, from an adjacent castle. I imagine highly concentrated gardens were where people liked to walk around. Ninna-ji represents the Shingon sect, which is from an esoteric Buddhism. The gardens there have a different feel than what you’d find on an aristocrat or a daimyo’s estate. The areas that compelled Mr. Kumon—the entrance with the sea of pine trees, the north garden, the south garden—they each leave completely different impressions and seem to condense the world into a garden. Ninna-ji’s gardens are concentrated, but I feel like they’re made more for admiring than moving through.

Many of the photographs are close to the subject. Were you aware of the idea of “neighboring textures” by this point?

Kumon: By this point, certainly. I was already aware that I was photographing the details. And the building itself looked incredible, with the connections among buildings and all the details. Even looking at the low handrails, they’re made of both rounded and squared-off wood. Ninna-ji has a lot of things to note like that. It was great.

Yamaguchi: I noticed there were three different materials in similar gray tones adjacent to each other: the wooden planks on the benches, the curbstones, and the white sand. The handrails also signal their connectedness rather than demarcate one area from another. I find this kind of harmony and abstraction very pleasing to look at.

Kumon: There’s a point after you’ve circled and you can see the series of roofs. It’s a fascinating scene. Mr. Yamaguchi said that the roofs were sun-burned, and when I took a second look I noticed the tiles and patterns were different from one to the next.

Yamaguchi:

The proportions of the roofs are beautiful, to begin with, and they’re made of a collection of complex textures, even though they’re all the same material—wood. Complexity can seem like excess, but the roofs’ details hardly look decorative. They look very simple. The shapes are a little different, and if the shapes are similar then the materials or sizes vary, but they all come together in harmony.

I think it might be characteristic of Japanese culture to create harmony out of complexity. For a modern cultural example, take AKB48’s wardrobe: every member wears something that matches their personality and is slightly different from what everyone else is wearing. But it complements the group as a whole. If you keep that in mind, you can look at AKB48 as a continuation of traditional Japanese culture. Quite interesting. Looking through the lens we’ve developed in this project, I think we can discover many more such connections in various situations in contemporary Japanese culture.

October 27, 2021