DUO’S JOURNEY

Kyoto Higashiyama Jisho-ji Temple

Higashiyama Jisho-ji Temple, also known as Ginkaku-ji Temple, was built by the 8th Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa in the Muromachi period (1336-1573). It would be a common impression that Japanese gardens, although they have circulation, seem to be slow to change and lack fluctuation. However, in Higashiyama Jisho-ji, each zone has its clear spatial characteristics, and if you walk around with this in mind, you will enjoy the variation. At the entrance, there is a narrow and high passage with no view of the surroundings, and once you clear it, there is an expanse centered on the main pond and sandhill, and by climbing further up, you get a bird’s eye view. It is rare among Japanese gardens to have such a straightforward three-level spatial structure. The garden is designated as a Special Place of Scenic Beauty by the national government and as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

What were you hoping to see at Ginkaku-ji?

Yamaguchi: I wasn’t expecting much, at first. I just thought I might find something if we went. I had been to Ginkaku-ji Temple when I was about 20, studying in the economics department, but I didn't find anything interesting at that time. When I went this time, I was of course able to see the place in a new light. The shakkei was difficult to grasp, but the views that Mr. Kumon determined for shooting were very striking. Shakkei is typically a feature that appears in the distance, but here, a mound called Kogetsudai is in the foreground, and it looked like a shakkei relationship. I got a feeling that this mound was the center of Ginkaku-ji. The man-made Kogetsudai was always in my line of sight, and the surrounding trees formed a relationship with it. This is what he was able to capture in the photograph. I realized that the interesting thing about Ginkaku-ji is the relationship between the Kogetsudai and its surroundings.

The thing that’s supposed to be in the distance is in the front. That is a strange shakkei relationship.

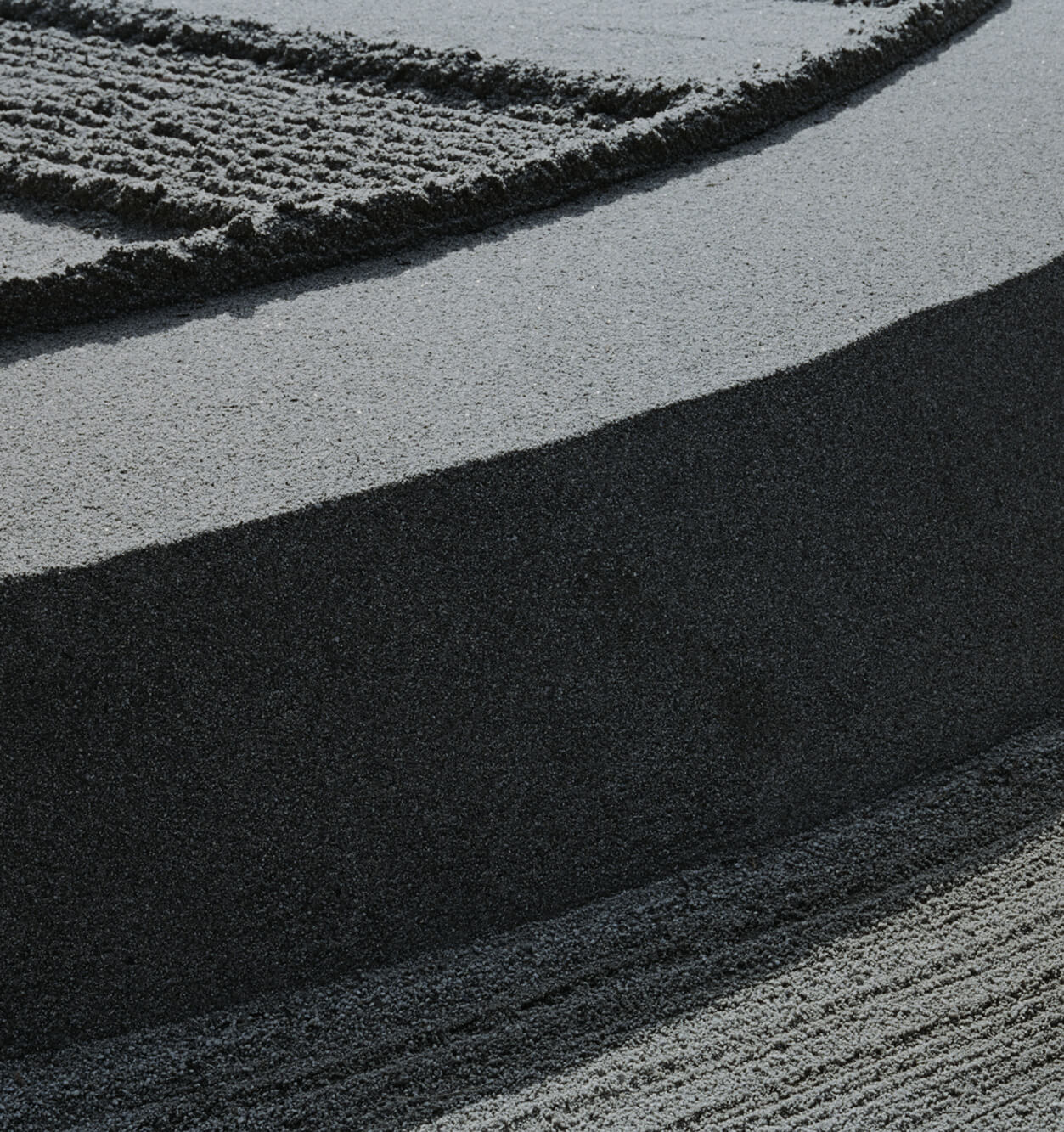

Yamaguchi: This is the sand around the Kogetsudai, and although it is the same sand, it has different textures and expressions. The same thing is done with the bamboo fence in Katsura-rikyu, although the sand itself creates the texture, rather than there being neighboring textures. It is only in photographs that you can see the difference by zooming in on and cutting out details.

Mr. Kumon, what was on your mind as you were shooting?

Kumon: At first, I thought, "Is this allowed?" It’s so different from anything I've seen before— it's too assertive. But when I thought about it, I realized that it was like a Zen question, because was a strong statement with no clear purpose. I thought it was interesting that it was in the center of the garden, and that we didn't know the purpose or function of the thing that kept coming into view. I thought it would be better to photograph it as something unexplained. Rather than framing the descriptive composition of the garden by including everything, omitting various elements allows the foreign object to stand out. I also liked the light at this time.

Yamaguchi: Within the context that the object doesn’t appear to be made for a purpose, I think that figuring out what the object is doesn’t change the way I see it. Rather, the value lies in how the scenery becomes special because of the presence of the object, and I think we should enjoy that. Knowing the origin of the garden will not change the scenery you see, and learning the background might even make it boring. Japanese gardens allow this. Mr. Kumon is a photographer, and he is a realistic person, and he examines things carefully and says things like "You can't see the moon from this angle." I wasn’t thinking about how things were, but more about how things might be.

Kumon: I asked Mr. Yamaguchi a question when we were there. I asked him what this meant. He told me that it didn't matter, and I thought, "I see." I don't need a purpose or historical background at all. I realized that what was more important was how the garden has been viewed throughout past eras, and how I was viewing it now.

October 27, 2021